Efficient and Effective Learning by Providing Models

The fifth principle of Landmark’s Six Teaching Principles is to provide models. The use of models helps us learn efficiently and effectively. From infancy onward, we all need models to learn new skills. Infants’ babbling mimics the sounds of caregivers and lays the foundation that enables them to develop spoken language. Children learn by watching models and mirroring behaviors—from learning to dress themselves to learning to swing on a swing set. Similarly, adults follow diagrams to learn how to repair a leaking faucet or watch videos of a dog trainer to learn how to get a pet to respond to commands. Models help us figure out what needs to be done and how to see a task through to its completion.

Executive function researchers, such as Russell Barkley (2019), assert that the ability to picture the steps required to reach a goal is a main function of the executive functions. Further, noted executive function coach and expert Sarah Ward (2014) outlines that without a model or a clear vision of the end goal, students “are open to distraction. When these children go into their bedrooms and see books, Legos, and a laptop, they easily disengage from the goal of getting ready.”

Providing models on how to produce the expected work, or how to get ready for school or class, supports students’ language and executive function skills. Research on learning and learning disabilities supports the inclusion of models in the classroom at all levels.

Specifically, providing models can boost student participation during class discussions. To create a clear picture of what a discussion is and what it is not, educators should facilitate a conversation with students about the distinction between a discussion and a conversation. Teachers can guide students to the conclusion that a conversation has no goal or topic, often wanders between different topics, and frequently uses informal language. On the other hand, a formal classroom discussion typically has a clear goal, a topic that connects to an overall unit, and requires that students reference texts or sources to back up their thinking. Additionally, teachers can highlight that a formal class discussion demonstrates critical thinking, provides opportunities to share novel perspectives and ideas, and enables them to build on each other’s ideas to reach new conclusions.

Teachers can also show videos that model the above criteria to provide a visual of why they are the foundation of an excellent academic discussion. Some ideas:

In addition to defining an academic discussion, teachers can also explicitly teach phrases that students can use to encourage discussion and respond appropriately to peers. These phrases can be shared as a handout or a reference on the wall in the classroom.

|

Expressing an Opinion:

|

Predicting:

|

Asking for Clarification:

|

Paraphrasing:

|

Soliciting a Response:

|

Arguing for / against:

|

Comparing It:

|

Making Connections:

|

Once teachers have established that students have a clear picture of what contributing to an academic discussion looks like, they can establish models for both teacher-led and student-led discussions.

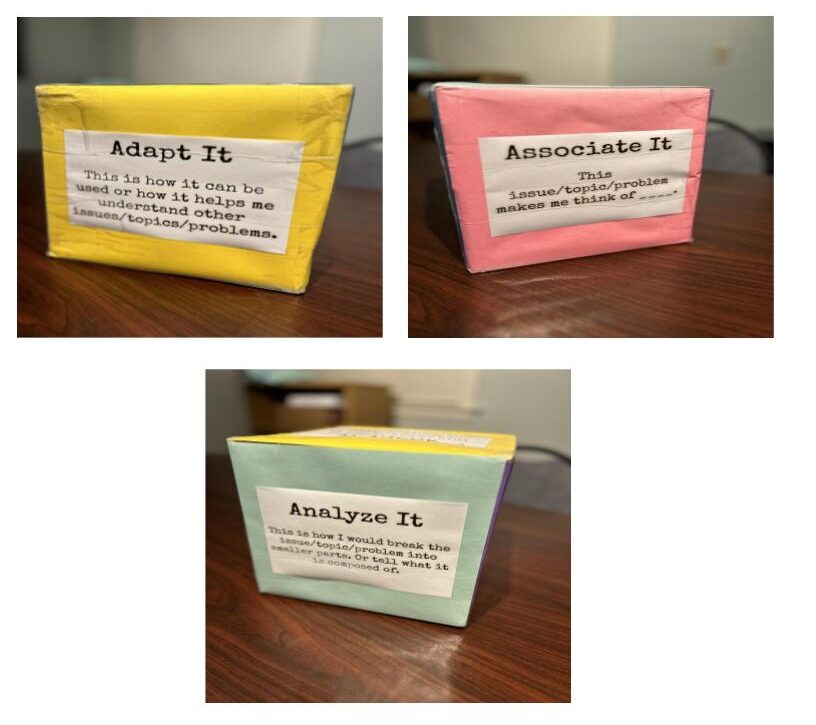

For all discussions, educators should communicate clear goals. Goals might include the number of times each student should speak and how many times students should directly reference the text. Teachers should also clearly outline how students should acknowledge someone who wants to speak, such as raising hands or passing a ball from speaker to speaker. Additionally, as a way to help students contribute effectively and respond to each other, teachers can put the above phrases on dice and have students answer based on how the die lands.

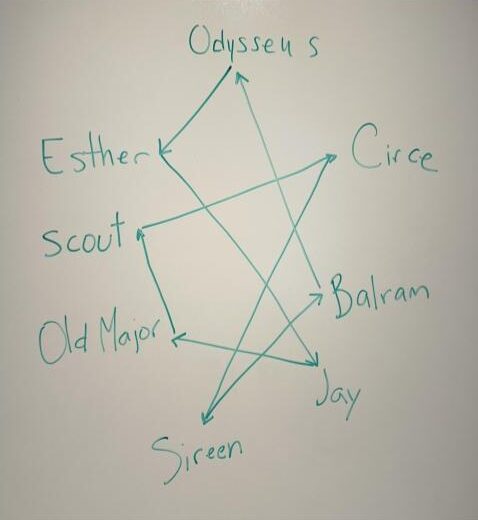

To assist purely student-led discussion where the teacher acts only as moderator or timekeeper, teachers can use The Table Discussion Tracker from The Phillips Exeter Academy Harkness Institute. The Table visually tracks the path of discussion and tracks participation. The teacher puts students’ names in a circle or the shape of a round table and tracks their participation.

Providing models is an essential instructional strategy to support students with dyslexia and other language-based learning disabilities (LBLD). In early elementary school, many models for academic expectations are provided; however, as students move through school, it becomes less common for teachers to provide models for academic skills. Educators may ask middle or high school students to engage in a discussion or “take notes,” for example, and there is often the assumption that students of this age already know the skill. Thus, teachers do not explicitly teach it or provide a model. However, models are valuable learning tools for students of all ages.

References:

Barkley, R. (2019, January 14). What Is Executive Function? 7 Deficits Tied to ADHD. ADDitude. https://www.additudemag.com/7-executive-function-deficits-linked-to-adhd/

Harkness Teaching Tools. Phillips Exeter Academy. (n.d.). https://exeter.edu/programs-educators/harkness-outreach/harkness-teaching-tools

Ward, S. & Jacobsen, K. Staying a Beat Ahead (2014). CHADD. https://chadd.org/attention-article/staying-a-beat-ahead/