Flipping the Bottom-Up Approach

I had a recent discussion with a tutor who mentioned she was about to teach writing multi-paragraph essays to a freshman in high school. This was uncharted ground, i.e., subject matter that was new to her, and she asked if I knew good sources for curriculum guidance where she could read best practices and then break down steps to impart to her student.

The more we talked, the more appropriate a top-down approach seemed. Micro-uniting in a step-by-step sequence is a well-trodden path for Landmark teachers, but approaching unfamiliar material with an older student made me wonder: Had she considered the benefits of flipping the bottom-up approach for one that challenged both her and her student to take a collaborative journey?

Ultimately, they planned to identify several effective essays, read them together, and then take several instructional sessions to reverse engineer them. How did the authors accomplish what they set out to do? Why did their finished products achieve that goal?

Teacher training models where component skills and content are acquired and then passed on encourage us to think “bottom-up” as educators. There are many benefits to what might be termed bottom-up teaching: the inductive practice of introducing specific skills in sequence and with abundant, success-oriented practice. A teacher leading her students on this journey often finds it helpful to set a clear goal, an objective on the horizon identified as the purpose for learning the material at hand. Students expect learning to be useful. A pragmatic goal is a key motivator so that they stay on course for the remainder of the unit. Thinking about organizing such a teaching approach resembles assembling something: identifying parts and tools needed to work with those parts, practicing the application of this knowledge, and eventually producing a product, perhaps a complete sentence, a multiparagraph essay, the answer to a math problem, the successful completion of a science experiment, or a unit test in social studies.

But what if this approach was varied with one that took a top-down or deductive approach? In this ‘reverse-engineered’ lesson, a teacher might consider jumping to the finished model, taking a giant leap of faith toward that once-distant goal and making that the starting point for a journey of analysis to see how and why it evolved.

In fact, considering both bottom-up and top-down approaches are valuable perspectives when taking into account the age, learning style, history, and special needs of our students, as well as the curriculum goals for our class. For students who are younger or more distractible, or who are confronting a new subject, teaching inductively from the bottom up is likely to be the best fit. The introduction of single micro-units of content with abundant practice in increasingly familiar contexts makes sense for language arts and math learners just being exposed to basic operations with text and numbers. Effective bottom-up teaching is hierarchical, carefully sequenced, and structured to provide a success experience. Teachers naturally gravitate toward leading this forward journey of discovery, and mastery can be overlearned as basics are applied repeatedly in a variety of contexts, modalities, and venues.

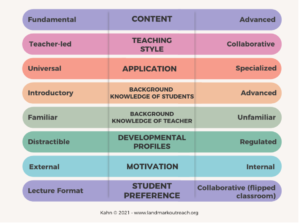

Consider the act of teaching, and the following scales of possibilities:

This is a partial list of determining factors that might inform a bottom-up vs. top-down teaching structure. Add to this the spectrum of learning styles evident in any class grouping, including the preference of some students for auditory, visual, or haptic approaches, and we’re presented with compelling reasons to vary our overall presentation style.

As we consider this host of variables, each approach may prove more or less matched to the context of the moment. As an example, a teacher presenting content to younger students in a class where capturing attention and external motivating tools are key strategies may well gravitate to a recipe-for-learning, bottom-up approach. Contrastingly, a teacher whose students have had a fair amount of previous exposure to the subject, whose attention levels are more regulated due to developmental profiles or internal motivation, and who are preparing for transition to the more collaborative style of a team approach may choose a top-down model; one where the finished product is examined and reverse engineered to see what the components of an excellent outcome are, and how they were generated and integrated.

Questioning our initial assumptions about the approach to a unit may lead to interesting choices for activities and style. Some approaches seem like a natural fit: literacy skills may need to be bottom-up to start; anatomy (dissections) in science are likely top-down. Less obvious: Rather than a chronological march from past to present, a top-down lesson in Social Studies might well start with an event, some legislation, or a sociological trend and look for the historical and cultural underpinnings that led to the moment in time. Consider also what bottom-up teaching would look like for the older learner? And what top-down might look like for the younger learner?

Varying bottom-up and top-down approaches has the added benefit of reminding us to differentiate our classroom as we individualize for a variety of learners. Analyzing learners’ readiness for each approach can lead to useful insights and a variety of teaching styles more likely to match the needs of our students.