Developing Phonemic Awareness

Did you know that a six-month-old baby can tell the difference between two words that differ by one phoneme, such as “pat” and “put”? They can make this phoneme discrimination because phonemes are the “building blocks” of spoken language, and the phonological processor in the brain is designed to automatically notice these differences in order to gather meaning from what was said (Moats and Tolman, n.d.). While babies have this amazing ability early on, it takes a few more months for them to make the connection between these sounds and language/meaning. Moreover, while they can discriminate between sounds, they do not yet have the metalinguistic awareness that these phonemes can be separated and manipulated. This more complex skill, typically developed between the ages of 4-9, is what we call phonemic awareness.

David Kilpatrick (2016) defines phonemic awareness as the ability to notice that spoken words can be broken down into smaller parts called phonemes (p. 13). Louisa C. Moats (2010) also describes it as “the conscious awareness that words are made up of segments of our own speech” (p. 277). It is a subset of the term phonological awareness, which is the ability to both recognize and move around sounds within spoken words and sentences.

Here are some examples: the word ‘kite’ has three phonemes /k/ /ie/ /t/ (the e is silent), the word ‘sled’ has four phonemes /s/ /l/ /e/ /d/ and the word ‘thorough’ has three /th/ /er/ /oe/. You’ll notice that the number of letters do not always correspond to the number of phonemes. How about box and fox: these three-letter words each have four phonemes: the ‘x’ contains two sounds: /k/ /s/. While there are 26 letters in our alphabet, there are approximately 44 phonemes (the exact number varies by dialect/accent).

Phonemic awareness is required for reading proficiency (Kilpatrick, 14). Students who do not possess this skill can likely hear well and can name letters in the alphabet, but would have little knowledge of what the letters represent (Moats and Tolman, n.d). Students need to be able to separate phonemes from one another so that they can connect these sounds to the alphabetic principle and ultimately decode words. This link is known as phonics: the skill of sounding out new words in print, or in other words “the study of the relationship between letters and the sounds they represent” (Moats, 28). This is how phonemic awareness intersects with reading: to make any sense of the alphabet principle, children need to realize that the sounds of the letters are the same sounds that they make in speech.

Some students will naturally develop phonemic awareness. These children typically go on to learn words quickly and do not easily forget them. For this group of students, receiving direct phonemic awareness instruction will only serve to more quickly develop their reading skills. There are many students who do not naturally develop it, including most students with dyslexia whose core reading deficit is in the area of phonological processing. Without direct support, learning to read can be a significant challenge. Direct instruction in phonemic awareness is absolutely essential in order for these students to successfully phonetically decode words.

Even though phonemic awareness difficulties are neurological in origin, David Kilpatrick (2016) argues that they are preventable and correctable (p. 13). Many schools discontinue phonemic awareness instruction by the second grade, but it is never too late to remediate phonemic awareness skills and there is “no statute of limitations on training phoneme awareness skills when they are weak” (p. 18). Providing targeted support in an individual or small group setting can help students make the phonological connection to words that did not come naturally early on. This will strengthen students’ word recognition abilities, thereby increasing their ability to fluently read text, and ultimately, comprehend what they are reading at increasing levels of text difficulty.

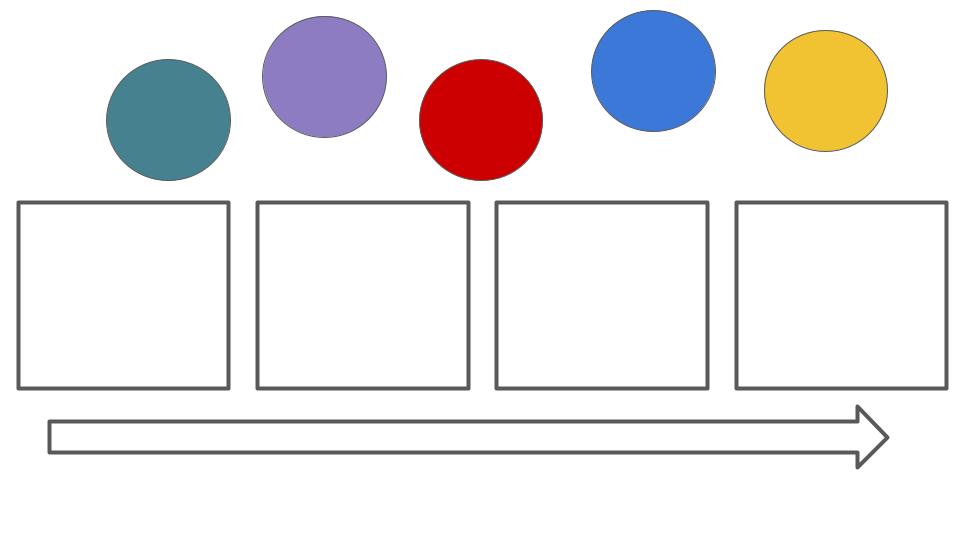

In addition to published reading programs that address phonemic awareness, there are many online resources available to support the development of this skill. Reading Rockets explains these concepts in depth and offers ideas for how to help students at home and at school. ”Freereading” offers free phoneme identification and substitution activities, after introducing early phonological awareness skills. The Florida Center for Reading Research is an excellent source for phonological and phonemic awareness activities, leveled for pre-k through 5th grade. Finally, “Elkonin boxes”, such as the example below, are a simple and effective resource for teaching phonemic awareness with manipulatives.

References

References

- FCCR Student Center Activities. Florida Center for Reading Research, Florida State University (2023) Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://fcrr.org/

- Kilpatrick, D. A. (2016). Equipped for Reading Success: A Comprehensive, Step-by-Step Program for Developing Phoneme Awareness and Fluent Word Recognition. Casey & Kirsch Publishers

- Moats, L., & Tolman, C. (n.d.). Why Phonological Awareness is Important for Reading and Spelling. Reading Rockets. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.readingrockets.org/article/why-phonological-awareness-important-reading-and-spelling

- Moats, L. C. (2010). Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers (2nd ed.). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Phonological Awareness Activities. FreeReading. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.freereading.net/wiki/Phonological_Awareness_Activities.html

- Phonological and Phonemic Awareness. Reading Rockets. (n.d.). Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.readingrockets.org/helping/target/phonologicalphonemic