Writing is Challenging for Students with LBLD

If you ask a room full of middle school students with language-based learning disabilities (LBLD), “Who here struggles with writing?”, inevitably nearly every hand will fly up. I ask my students this question every year, not to start the year on a negative note, but to reset their thinking about writing by helping them identify WHY it is so difficult for them. We talk about all of the different sub-skills that go into writing, which are hardest for each of them, and which parts of writing they actually do enjoy. It turns out, a lot of middle school students with LBLD love some parts of writing – they enjoy being creative, thinking deeply about topics, and coming up with arguments. Our goal, then, is to help them channel these strengths while also supporting them in the areas of writing that are harder for them.

There are plenty of articles about all of the reasons why writing can be so difficult for students with LBLD, from basic transcription skills to idea generation to proofreading to the numerous executive function demands underlying the entire writing process. Even just reading and understanding the prompt is a skill that can require direct instruction – I’m sure I’m not the only one who’s been pleased with a student’s independence during a writing assignment only to realize upon reading their final product that they actually didn’t understand the prompt at all!

Now let’s think about middle school students in particular. They have been in school long enough to have developed strong ideas about what they are and are not good at. They may at times exhibit complete and utter “shut down” when asked to complete a writing assignment. Finally, by middle school, content area teachers often assume that students possess the skills required to write a paragraph or open response in their science and social studies classes and no longer need to have this task broken down – resulting in higher writing demands for students who may or may not possess the requisite skills to complete them.

Middle school students, however, also have a hidden superpower: They are creative, passionate, and really, really great at arguing and imagining. They have so many strengths that can be channeled while writing to help them navigate their challenges – when given direct instruction, mentor texts and choice, and support for language demands at each phase of the writing process.

So How Can We Help? – Language-Based Writing Instruction

First and foremost, students need a solid foundation in the writing process and the knowledge that, for each assignment, they can and should follow the same basic steps. In my own small-group language-based ELA classes, I plan writing assignments to include scaffolding for students’ language skills at the word, sentence, and paragraph levels. Research also shows that providing mentor texts to pair reading and writing assignments is extremely effective and that, rather than separating time into a reading block and a writing block, these processes should be integrated to increase both engagement and skill development (Shanahan, 2017). Finally, with middle school students, providing choice is a key element of that most elusive yet important factor: buy-in! I’ve found that the same students who would shut down if assigned a five-paragraph research paper will engage with the process when asked to write a five-paragraph article, complete with text features like headings and pictures, on any topic of their choice.

What Does This Look Like? – A Sample Assignment

My seventh-grade students recently completed a unit called Character & Conflict as part of our ELA curriculum, focusing on how authors create characters and develop conflict in literature. Our mentor text for this assignment was the short story “Sucker” by Carson McCullers. During the unit, students learned to identify examples of both direct and indirect characterization. Our daily vocabulary words related to emotions or attributes for each character, and we engaged in word-level work about emotion/descriptive words.

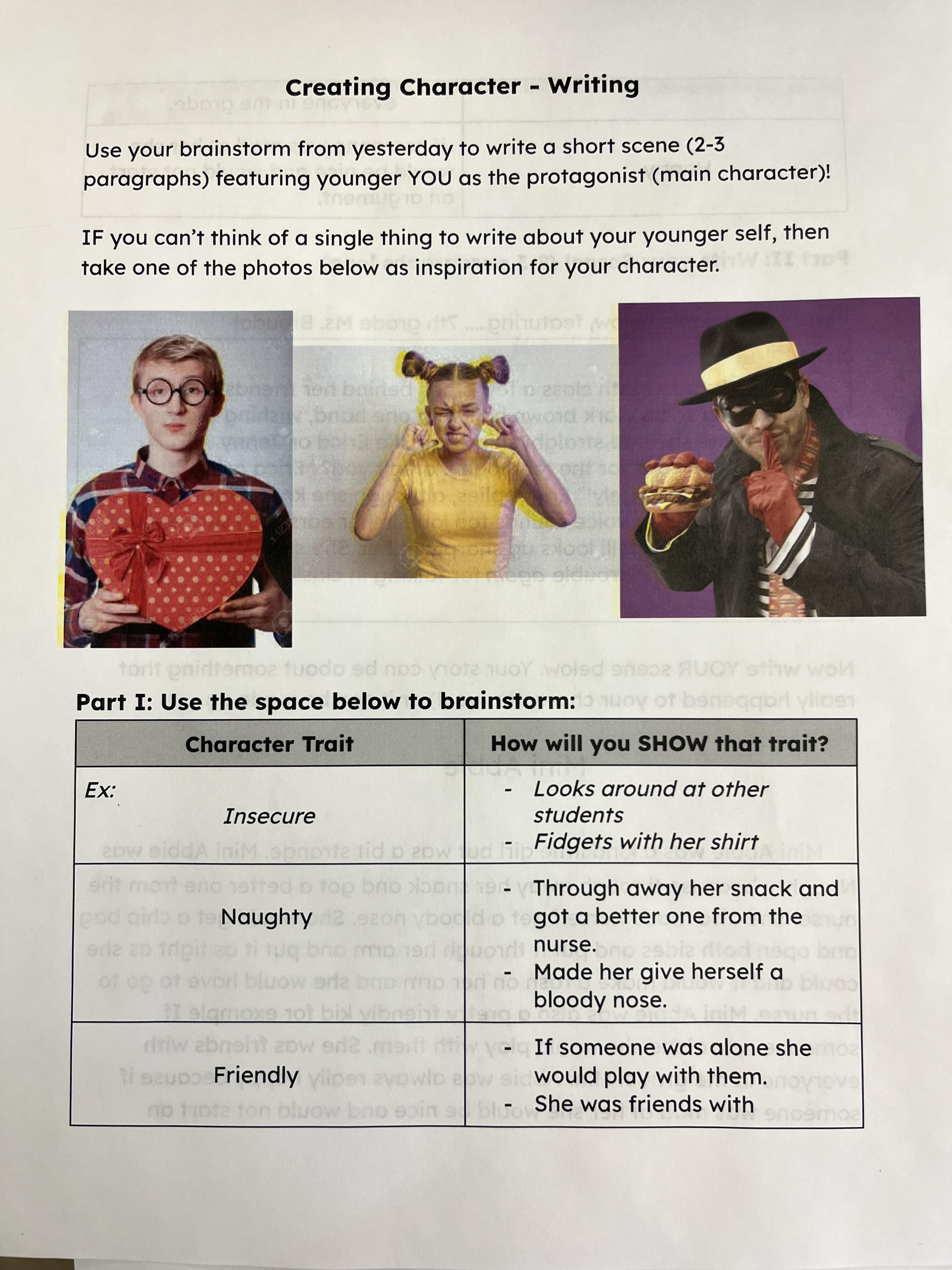

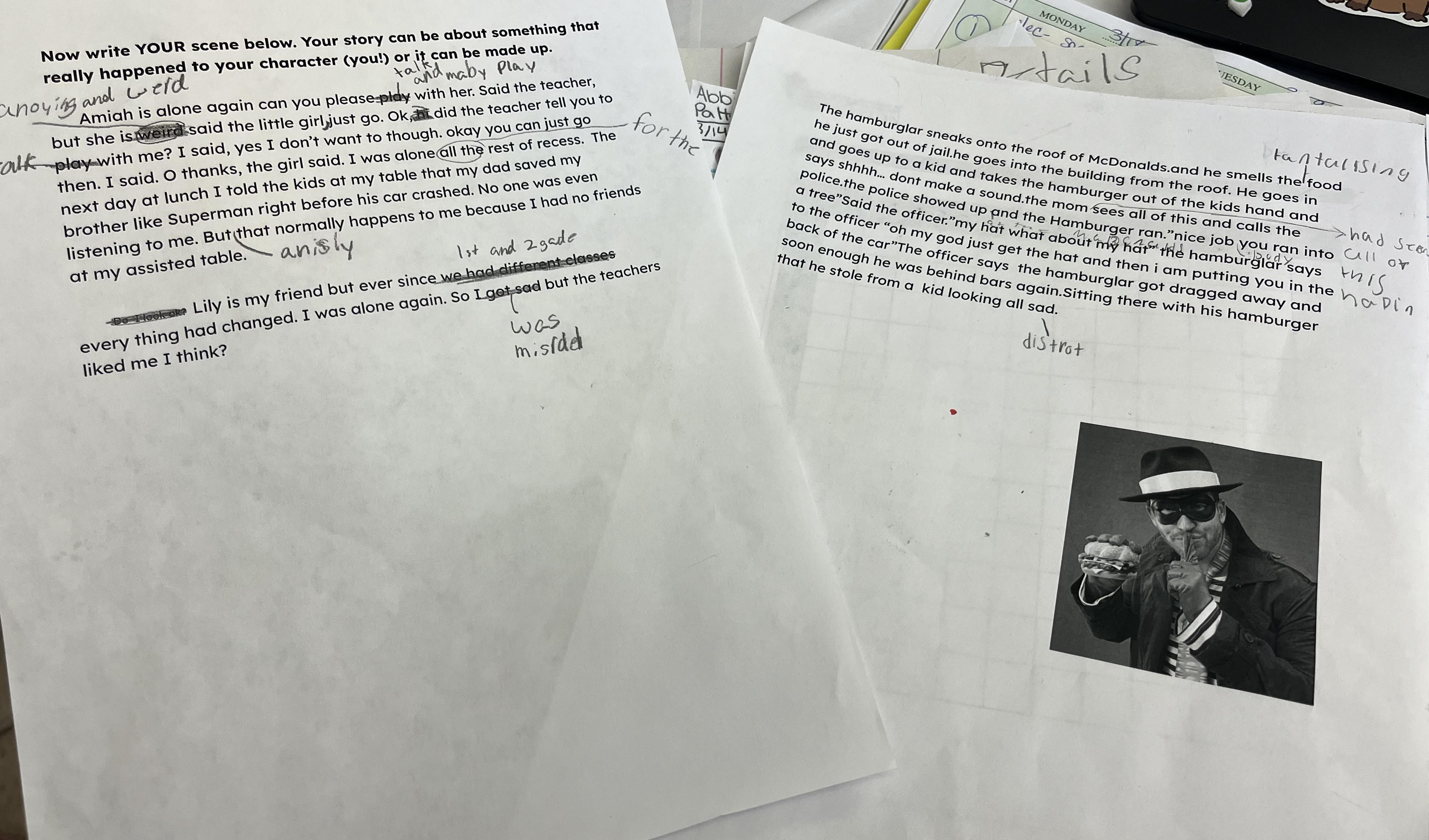

To reinforce the concept of characterization through writing, I asked students to create a character based on their younger self. I thought they would all enjoy writing about their past selves, but during our first step, Brainstorming, it became clear some students couldn’t think of or remember anything. I made a slight pivot and presented them with more choices in the form of some goofy pictures (including one of McDonalds’s Hamburglar), and suddenly each student had at least one character they were excited to create.

Word-level and sentence-level work can all take place during the brainstorming phase, as well as the second step of the writing process: Organizing. Although students do not need to write complete sentences during this phase, they have the opportunity to expand their ideas with the scaffolding provided on their graphic organizer – all of which makes turning those ideas into sentences and then into paragraphs so much easier because they have a starting point. The ideas, I always tell my students, are the real point of writing – and they are all excellent at coming up with ideas.

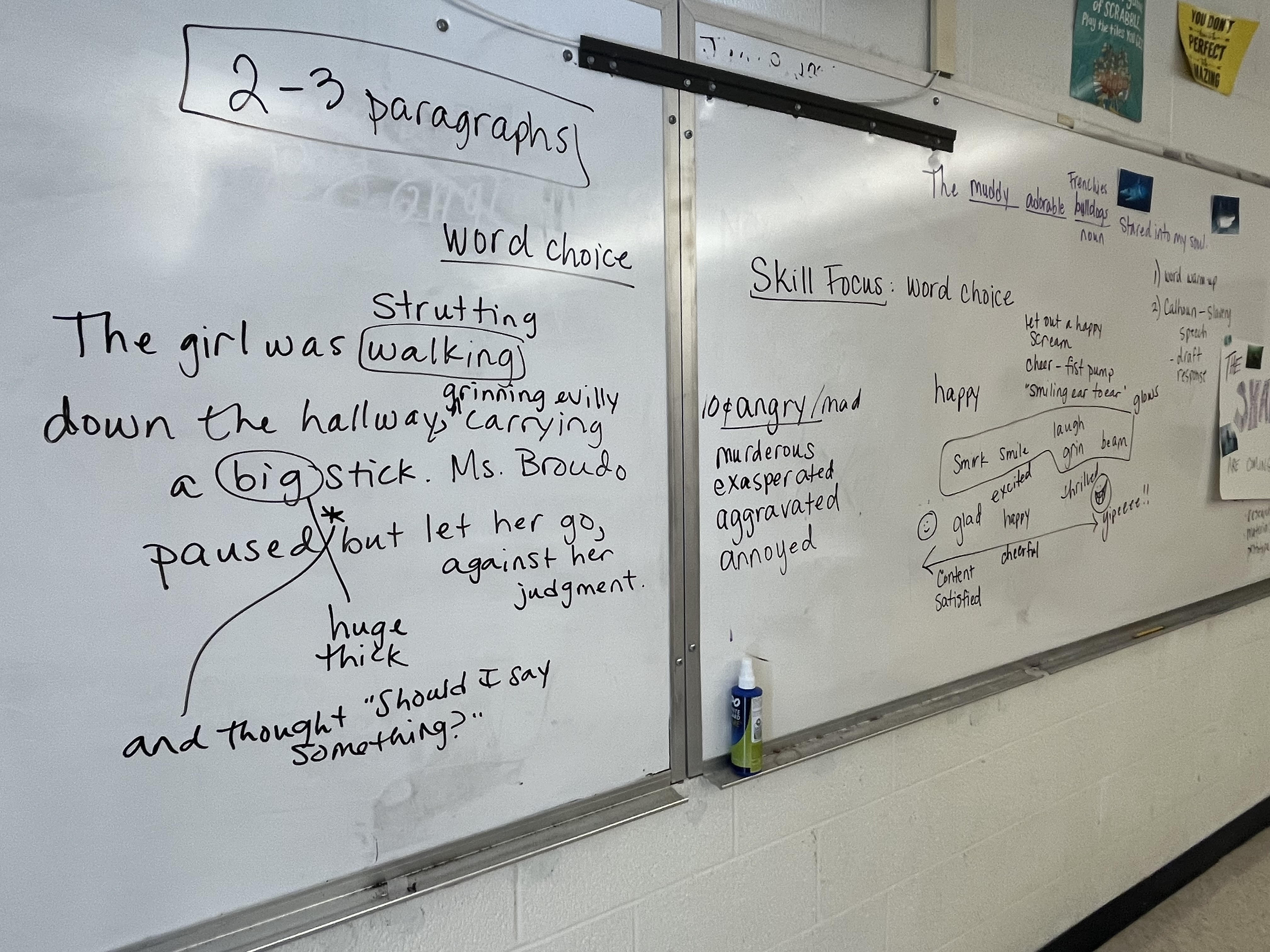

With a detailed graphic organizer, the next step – Producing a Draft – is less overwhelming. Students can simply cut and paste their ideas from their graphic organizer into a blank document, and then polish them up, turn them into complete sentences, and add details – editing as they go without even realizing they are doing so. This is a good time to add in some sentence-level work by modeling sentence structures, sentence combining, writing a topic sentence, or revising for word choice as a quick warm-up before students get started.

The fourth step, Editing/Proofreading, is made more engaging through the use of interactive proofreading checklists where students have concrete tasks. For our characterization activity, I chose to focus on word choice since we had done a lot of word-level work on “emotion words” and the incorporation of our vocabulary words into our writing. I modeled how we might add detail and more descriptive verbs in a sample paragraph, then asked students to do the same in their piece – as well as edit for basic capitalization, punctuation, and clarity with a checklist.

Students then incorporated their corrections into the fifth and final step of the writing process, Producing a Final Draft. By revisiting their piece so many times, using a mentor text to help reinforce key ideas, and making the process creative, fun, and filled with choice, my students were able to produce excellent examples of characterization that reflected their understanding of how to create a character in literature – a skill will reinforce their reading comprehension skills as well as their writing skills and the entire writing process.

References:

Shanahan, T. (2017, February 23). How should we combine reading and writing?. Shanahan on Literacy.https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/how-should-we-combine-reading-and-writing