Help Students Manage Materials

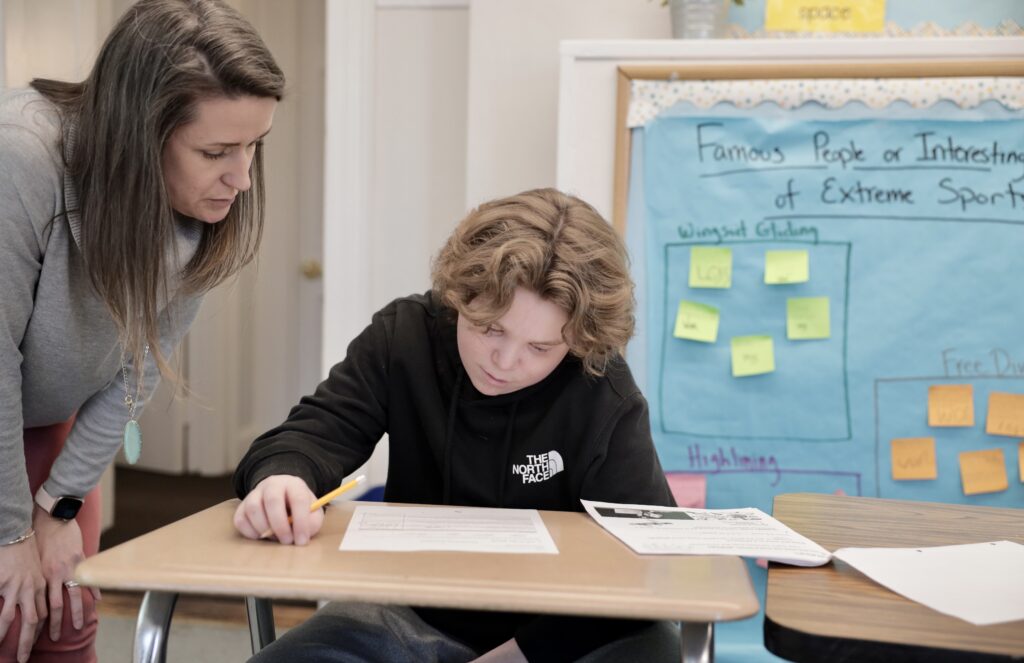

Most social science classes convey information through reading, and mine is no different. I assign students a reading on a topic, they read it, and then in class, we discuss it, sound familiar? Over the years, I’ve stopped using a history textbook for those readings because I wanted my students to leave my class with a more nuanced perspective of world history that a textbook doesn’t always provide. This allowed the class to dive deeper into eras and movements in history and for ninth graders to understand that history, even ancient history, directly informs the present. An unintended consequence of this way of teaching history was that there was a dramatic increase in the volume of loose papers my students needed to keep track of and file. It created a paper black hole in the bottom of students’ backpacks: readings, note sheets, more readings, quizzes, more note sheets. Any important material that they might need to use to take a unit test or complete other work was frequently lost, only to be unearthed months later next to a moldy banana. I didn’t want to go back to the textbook, but I also needed a method to help them keep paper and important materials organized and easily accessible.

I needed to reduce the amount of paper, or more directly, I needed to reduce the amount of materials that they could lose. I’d seen the Landmark High School math department create live reference sheets called flappers where students added formulas and concepts to index cards taped to a sheet of paper as they learned them. It helped them remember important information that was essential in moving from year to year in mathematics and it gave them a model for differentiating between relevant and irrelevant information. I thought that this might also be something that would be adapted to world history.

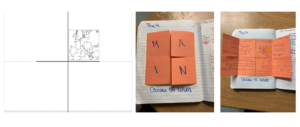

I expected implementing this idea to be tricky. After all, PEMDAS fits on an index card, but history doesn’t simplify quite so neatly. I decided that I could reformat my notes so that students could gather and collect all the necessary main ideas and details in a composition notebook. I also recreated note sheets to be more interactive so that students would be able to quiz themselves on the content. For example, when we learned about imperialism, I created a guided note template that they glued into the notebook before they left class to work on that night. As an in-class activity, when we studied the four main causes of World War 1, students cut across the dotted lines to create a flapper in their notebooks on the main ideas of the concept, including a map that they could color and highlight important regions. Students wrote the main ideas on the outside of each section and filled in the details on the inside based on what I wrote on the board. Every time we added to their notebooks, students were immediately a bit more engaged in the discussion and excited to look back on their progress.

One of the most valuable parts of using a composition notebook is that organizing and making a collage with the templates for notes becomes an integral part of each lesson. My lessons automatically became more multi-modal and students responded consistently. Students also directly interacted with how information is best organized on a given topic and learned to distinguish irrelevant and relevant details. Because important materials are physically attached to the notebook and are not easily lost or misplaced, students no longer have a deluge of papers in their binders. Initially, I was worried about some students losing their composition books, but I’d like to believe that their investment in the creation of the notebook led them to understand its importance and in general. I find that students are good about keeping track of it.

Now that I have introduced this system to my class, I can’t imagine returning to how I handled note-taking before. Even the most disorganized and disengaged students find a sense of pride in their notebooks and remember information far better than they did before.