Back to Basics

In many ways, for educators, the start of the school year is our new year. Similar to New Year’s Day, at the beginning of the school year, I find myself in conversations about setting goals and in discussions about making resolutions to implement a variety of new policies and initiatives. In the midst of these new initiatives, I try not to lose sight of the basics.

At Landmark School, our instruction is guided by the Language Box™ and Landmark’s Six Teaching Principles™. As we design lessons to support our students who struggle with language and literacy skill acquisition, these two tools are at the heart of our instructional practice. Most importantly, they enable us to effectively scaffold instruction and create classroom environments that relieve students’ cognitive load, freeing up their energy so that they can engage in purposeful learning.

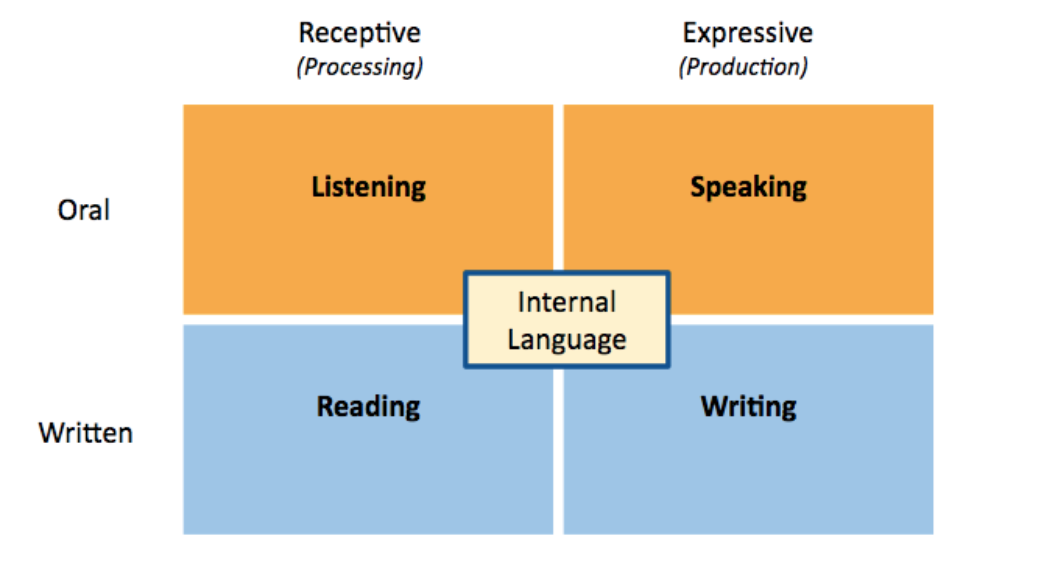

The Language Box™ is a speech-language construct that considers the four interrelated areas of language: listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

The Language Box™ also includes “internal language” at the center of the figure. This is the ability to engage in internal dialogue with oneself and demonstrate metacognitive skills. For students, this might be pausing in the middle of a reading assignment to ask: “Does this make sense to me?” or “How does this reading fit within the larger unit?” Supporting our students requires that we model internal language and activate all the areas of language in our lessons.

The Language Box™ also includes “internal language” at the center of the figure. This is the ability to engage in internal dialogue with oneself and demonstrate metacognitive skills. For students, this might be pausing in the middle of a reading assignment to ask: “Does this make sense to me?” or “How does this reading fit within the larger unit?” Supporting our students requires that we model internal language and activate all the areas of language in our lessons.

At Landmark School, Landmark’s Six Teaching Principles™ also guide our instruction:

- Provide opportunities for success

- Use multisensory approaches

- Micro-unit and structure tasks

- Ensure automatization through practice and review

- Provide models

- Include students in the learning process

While all of these teaching principles are interwoven throughout our lessons, at the start of each year, I remind myself to focus on the fourth principle: Ensure automatization through practice and review.

Repetition, particularly for struggling learners, is critical to their ability to master skills. Handler and Fierson have shared that students need 40 repetitions to move recognition of orthographic patterns into long-term memory. Their research (2011) shows that “Experienced readers use the whole-word method and will quickly recognize most words as individual units. Average readers require 4 to 14 exposures to a word before it becomes a sight word, whereas students with learning disabilities may need up to 40 exposures” (p. 6). McCormick and Zutell (2014) share this assertion and reinforce the importance of upward of 40 exposures to a word before it becomes a part of students’ sight vocabulary (p. 292).

More importantly, the number of repetitions must be attentive. The student must be aware of that exposure in an intentional way. Meaning, that just exposure is not enough. Shanahan (2016) writes: “Repetition helps—you can build some kind of word memory through rote repetition. But to develop a powerful, flexible understanding of words, you need to ask yourself, ‘repetition of what?’” The repetitions must be purposeful.

Although, to my knowledge, this research has not yet been generalized to students’ acquisition of organizational routines, there’s a case to be made that students need this level of repetition in all areas.

One of my mentors and colleagues once asked me to imagine my students’ day. In most cases, in grades 4 through 12, students are transitioning between seven classes with a minimum of seven different educators, and within each class, they are moving between a variety of different activities. In each of these settings, they are most likely faced with different classroom routines, materials needs, and organizational norms.

After a week or two, many educators become frustrated when students are still struggling to independently get ready for class and move between activities. However, many students probably need 40 exposures to these organizational routines. This requires 40 days of instruction per class – essentially, students will need until at least Halloween to achieve independence.

My colleague then posed the question: What if we collaborate across grades and grade levels? At Landmark, we work to maintain a shared binder or folder system, and we talk to one another about the setup of our Google Classrooms. By creating consistency across our students’ day, we can achieve the required 40 exposures much more quickly and help students automatize routines within a few weeks.

Whether the goal is vocabulary acquisition or the ability to organize a binder, repetition is integral to independent learning. Similarly, promoting metacognition in the development of both language and organizational routines becomes a simple way to start off the school year with essential skills.

References

- Handler, S.M. & Fierson, W.M. (February 28, 2011). Learning Disabilities, Dyslexia, and Vision. Pediatrics Vol. 127 No. 3.

- McCormick, S. & Zutell, J. (2014). Instructing Students Who Have Literacy Problems. Pearson, 7th Ed.

- Shanahan, T. (March 6, 2016). How Many Times Should They Copy the Spelling Words? Shanahan on Literacy. Retrieved https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/how-many-times-should-they-copy-the-spelling-words