Include the Student in the Learning Process

As an academic advisor at Landmark High School, I was lucky to have many students who would seek me out to celebrate or lament an assignment grade. When I would ask them what led to that success or lack of success, they weren’t always sure. For many, they wanted that to be the end of the conversation. For me, it was the beginning. “What strategy did you use to study?” I might have asked. Or, “Is there a rubric we can look at together? Did your teacher give you any feedback?” Regardless if it was a “good” or “bad” grade, these questions mattered. In these moments, I wanted them to pause and reflect.

Self-reflection is not easy. Our ability to non-judgmentally reflect on our needs, habits, and behaviors and then adjust our actions according to the task at hand is ongoing work for most adults. The more awareness we bring to this process – in other words, the more we engage in metacognition – the more grounded and successful we will feel.

Think about something you find challenging. Filing your taxes? Cleaning out the fridge? Planning a curriculum unit? Executing a lesson plan? How often do you stop and assess your strategies when completing these tasks? If we think about how difficult it can be to self-reflect as adults, it can give us insight into why it’s so helpful to foster these skills in our developing learners.

Our ability to reflect can also be understood within the context of executive function. Simply put, our executive function skills help us engage in goal-directed behaviors (Dawson and Guare, 2018). When working fluidly, executive functions coordinate to help us set a goal, sustain our attention and effort throughout, inhibit our responses to distractions, remember the necessary information, manage our emotions along the way, and flexibly adapt our actions and behaviors as needed (Dawson and Guare, 2018). At any stage of the process, pausing to reflect helps.

Now that I am an instructional coach and consultant for Landmark Outreach, I get to see the power of reflection across grade levels. Consider these three scenarios that I observe in Massachusetts’ classrooms spanning elementary through high school.

Reflection Tied to Goal-Setting

It can be helpful to engage in goal-setting at the start of the year or the start of any new term.

To effectively set goals, first prompt students to engage in self-reflection. When I had my own classroom, I would ask my students to write down one thing that they felt good about that term and one thing they didn’t feel as good about. Instead of crafting goals based solely on the “problem” areas, I prompted them to build on the moments of success they experienced in my class. Did they feel particularly good about a writing assignment in that unit? What could they carry forward to the next term based on that success? What incremental change could they make to feel even better about it next time? Now, when I observe classes grounded in this kind of reflection tied to goal-setting, it’s clear that the students feel more involved in the learning process overall.

Reflection Tied to Self-Monitoring

When we assign an in-class task for students, we are actually giving them a goal: complete x task in x amount of time. Simply changing the language we use in these moments can be helpful. Instead of saying, “Complete this worksheet,” we can frame it as a question: “What goal do we have for this period?” Students are then the ones stating the desired goal (and reflecting on what they need to accomplish). This also allows for differentiation, as some students may have different task completion goals depending on the timeframe.

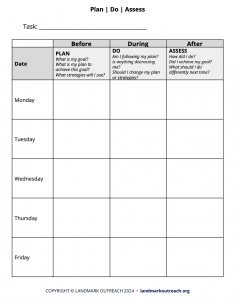

When assigning independent in-class work, I often used a planning framework called Plan/Do/Assess, created by a colleague here at Landmark and adapted from Sarah Ward’s Get Ready/Do/Done. What I love about this plan is that it asks students to pause and reflect before, during, and after a task. We want to set the intentions clearly at the beginning, asking them not only what the goal is but also what strategies they will use to complete the task. Importantly, we stop halfway through the allotted time and ask students to pause and reflect again. Are they following their plan? Is there anything distracting them? Do they need to flexibly change their strategy? Finally, we again asked them to assess how they did at the end of the task. Did they successfully complete their goal? Were there any changes they would make in the future? Over time, they can begin to internalize these self-monitoring strategies, ultimately feeling more confident as learners (and saving time for teachers!).

When assigning independent in-class work, I often used a planning framework called Plan/Do/Assess, created by a colleague here at Landmark and adapted from Sarah Ward’s Get Ready/Do/Done. What I love about this plan is that it asks students to pause and reflect before, during, and after a task. We want to set the intentions clearly at the beginning, asking them not only what the goal is but also what strategies they will use to complete the task. Importantly, we stop halfway through the allotted time and ask students to pause and reflect again. Are they following their plan? Is there anything distracting them? Do they need to flexibly change their strategy? Finally, we again asked them to assess how they did at the end of the task. Did they successfully complete their goal? Were there any changes they would make in the future? Over time, they can begin to internalize these self-monitoring strategies, ultimately feeling more confident as learners (and saving time for teachers!).

Reflection Tied to Time Management

A key component of the Plan/Do/Assess template is stopping halfway through the allotted time of an activity and prompting for reflection. This strategy draws attention to the passing of time for our students. When so many struggle with time awareness, it can be helpful to simply name the passage of time (ideally paired with clocks for a visual aid). You can do this without using a more formal template. I’ve seen this integrated naturally into elementary classrooms. The teacher gives students 20 minutes to work on a group project and sets a timer for 10 minutes. When that timer goes off, the teacher then states, “You’re halfway through the time and have 10 minutes left.” If a student is struggling, this still gives enough time to effectively change their strategy or action. It also helps them practice time estimation and time management because they are prompted to reflect on their use of time.

While seemingly straightforward, students may initially struggle when we engage them in these reflection activities and prompt them to reflect on their academic behavior. For some, this can feel very challenging, and they need the process to be scaffolded. For others, it may feel uncomfortable. As I noted, reflecting on our own behavior can be tough – think back to the stress of tax season! By giving students practice, they can begin to internalize this process and become active, self-aware learners.

References:

Dawson, P., Guare, R., & Guare, C. (2018). Executive skills in children and adolescents: A practical guide to assessment and intervention. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ward, S., & Jacobsen, K. (2015). Cognitive Connections. https://www.efpractice.com/