“Every writing teacher should own From Talking to Writing. Full of wisdom gained from decades of teaching experience combined with deep immersion in research and theory, the authors provide guidance on the questions that arise in every writing teacher’s mind.“

– Dr. Leslie Laud, Director ThinkSRSD & Bank Street College of Education (New York, NY)

This new, significantly updated edition of From Talking to Writing offers welcome help for any educator working with students who struggle with writing and/or expressive language skills. From word choice to sentence structure and composition development, this book provides step-by-step strategies for teaching narrative and expository writing. The authors took the time to respond to some questions about their new book, as well as reflect on the best practices they have learned and developed throughout their teaching careers.

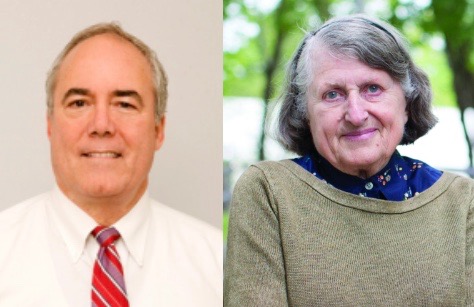

Terrill Jennings, a founding teacher of Landmark School, has taught students with dyslexia for more than forty years. Recipient of the 2016 Alice H. Garfield Award from the International Dyslexia Association, she has chaired the Language Arts department at Landmark’s Elementary•Middle School and co-founded Landmark’s Expressive Language Program.

Dr. Charles Haynes is a professor and clinical supervisor at the MGH Institute of Health Professions in Boston who has over thirty years of experience educating children and adolescents with dyslexia. A recipient of international honors and awards for his teaching, Dr. Haynes helped pioneer Landmark School’s Expressive Language Program.

Q: What was your most satisfying moment in teaching writing? What did you like best about being in the classroom? On the other hand, what was your most challenging moment?

Charley and Terry: Our happiest personal experiences have been struggling writers’ “Ah-ha!” moments, when students discover how a writing strategy unlocks their expression and lets them express their ideas. Our most challenging moments have been when we have been guilty of “dysteachia” – when our own teaching has been disorganized and inadequate to meet students’ needs.

Q: What are the main differences between the first edition of the book and this new one?

Charley and Terry: Our first edition sold over 5,000 copies, so we wanted to seek guidance before incorporating changes. A focus group of colleagues provided very helpful suggestions for what to include in the second edition, and we listened to them carefully and the second edition reflects these. Each chapter begins with a short case study and shows how the chapter’s content addresses the teaching problems posed by the case, and we have indexed each chapter to anchor to the Common Core State Standards. We also provide dialogues that illustrate how oral language practice can support students’ writing. People who buy the book are given a website where they can download the various templates and worksheets that are explained in the book. Also, since the first edition in 2002, we have learned a lot more about how to: (1) structure semantic feature analysis of vocabulary to support sentence writing, (2) leverage personal sequence narratives for teaching elaboration skills, as well as (3) support development of inter-sentence cohesion (flow of meaning from one sentence to the next).

Q: What was your inspiration for creating the templates and graphic organizers that are specific to this book?

Charley and Terry: Graphic organizers provide students with visual structures that guide their writing, and they are powerful and effective strategies. However, we discovered that these organizers alone were not adequate to meet the needs of our students. We saw that struggling language learners needed more help, so we provided more language support by embedding vocabulary boxes and sentence scaffolds within the templates. In addition, we broke down the exercises further so as to ensure students would achieve success. We also realized that, in order for students to own the strategies, they needed to be able to memorize them for independent recall.

Q: You both were at Landmark School at the beginning. What have you learned from spending an entire career supporting students with learning disabilities?

Charley and Terry: We have learned that students with learning difficulties provide a litmus test for how effective our teaching strategies are. These students are extremely sensitive to poor teaching approaches and techniques, and when these learners succeed, it is most likely because their instruction is of good quality – structured, systematic, and geared to multiple modalities of language (listening, speaking, reading, and writing). We have also learned that our field tends to self-select teachers who are mission-oriented, empathic and observant – some of the nicest people we have met work with students with learning disabilities.

Q: What role does metacognition play in helping students learn to not only be proficient writers, but independent in the process of expressing their thoughts in writing?

Charley and Terry: Development of metacognitive skills is at the heart of teaching and learning. Any of the “metas” (for example, metacognitive, metalinguistic, metaphonological, metasyntactic, metapragmatic) refer to the ability to be aware of and analyze nonverbal or linguistic patterns – the rules of language. When we teach students to recognize and reflect on sentence patterns, for example, their metasyntactic abilities allow them to self-regulate (monitor, formulate, and self-correct) their language.

Q: Executive function is one of the current buzzwords in education. How do you see your strategies and writing philosophies connecting to this trend?

Charley and Terry: The concept of executive functioning has been around for more than forty years, and if educators are trending towards thinking about the concepts, this is a positive sign. The expressive language methods in our book provide scaffolding for, and help to strengthen, executive functioning for language. Consider the example of a graphic organizer, or template, for an adjective + noun + verb + where phrase + when phrase sentence. In a class studying the theme of “fall in rural New England,” a student might follow this pattern to produce the sentence, Honking geese flew over our heads that fall afternoon. Students’ Initial oral and written practice using organizers or templates like this one helps them to internalize the pattern, aids their monitoring for that pattern, and supports their recognition and repair of errors. When the template is memorized, it becomes internalized as a plan that the student can rely on in future listening, speaking, reading, and writing activities.

Q: Is there a best practice or strategy for teachers who are starting to work with young children or students who struggle with the basics of writing? And is there a best practice or strategy for teachers who work with students who are ready to to begin the transition to college?

Charley and Terry: An adequate response to this question would be vast, so we will just suggest a few key points. Steve Graham and colleagues’ research indicates that for students who are old enough to grasp strategies, an emphasis on self-regulated strategy development (e.g., use of graphic organizers) is effective. In addition, whether a student is a child or an adult, it is critical to identify and work in their “zone of proximal development” (ZPD) – What has the student mastered? What are they struggling with? What scaffolding best helps them to learn what they need to know? In addition, teachers should keep in mind the critical roles that structured listening and speaking exercises can provide in development of (reading and) writing skills. Last but not least, a common mistake is for teachers to use non-thematic worksheets that contain semantically unrelated writing exercises. Optimal teaching should incorporate topical vocabulary and themes at the word, sentence, and paragraph levels. In sum, best practices in writing instruction involve teaching strategies that aid self-regulation, teach to the student’s ZPD, employ listening and speaking exercises, and incorporate topical vocabulary and concepts as material for language activities.

Q: Do you have any advice that you wish someone might have given you at the beginning of your career in education?

Charley and Terry: We both feel blessed – we have gotten good advice from excellent mentors throughout our lives! Based on what we have learned from our own experiences in teaching, here are a few tips for finding joy in your career:

(1) Seek out colleagues to work with whom you are stimulated by and who you enjoy being around.

(2) If you have a well-thought-out point of view, and your understanding differs from the more popular or prevailing view, don’t be afraid to “follow the beat of your own drummer”.

(3) When you discover that you enjoy a certain aspect of teaching and learning, find ways to explore, expand, and build on that interest.

We have each tried to live by these principles in our own way, and we have experienced (and continue to experience!) rewarding educational careers.