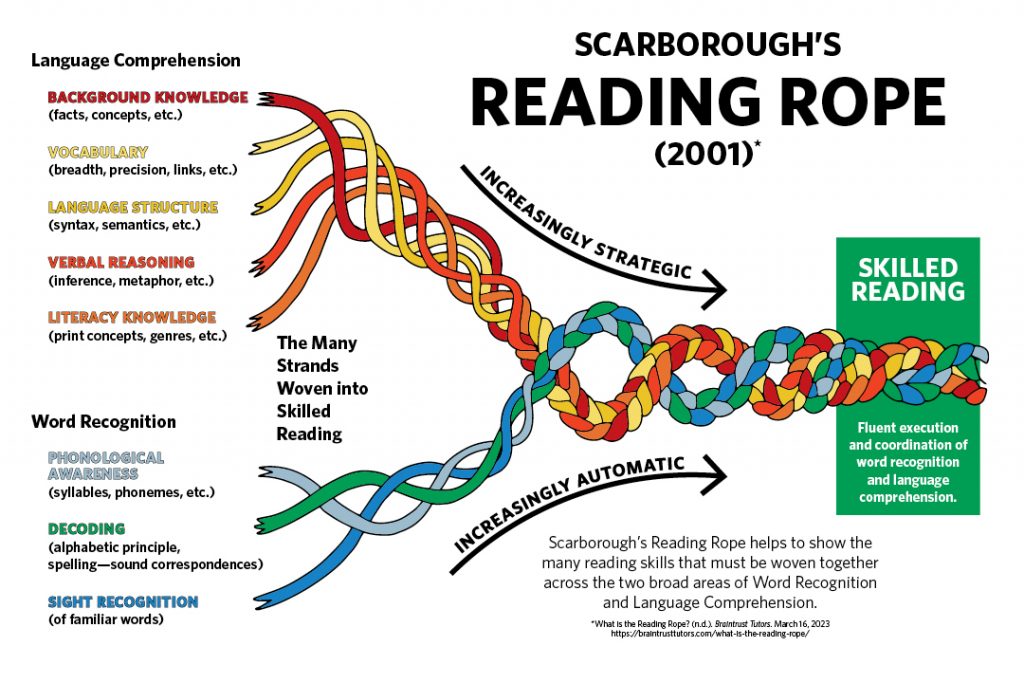

As students enter second grade, they transition from learning to read to reading to learn. The more students read, the more access and exposure they have to content and vocabulary. However, for students who do not make this transition and are still learning to read in the second grade and beyond, their access to critical background knowledge and vocabulary is significantly diminished. Many contemporary models of reading instruction, grounded in the Science of Reading—such as Scarborough’s Reading Rope—acknowledge the impact of limited vocabulary and background knowledge. Specifically, background knowledge and vocabulary are highlighted as essential language comprehension strands, demonstrating that they are critical pieces of literacy development. When students have reduced capacity in these two areas, their ability to understand what they read is reduced.

Supporting students with limited background knowledge requires thoughtful and explicit preparation and instruction. Active reading strategies often focus on what to do during reading, while comprehension assessments typically take place after reading through teacher-generated questions or summaries. For struggling readers, these strategies remain important to help them manage and organize their understanding of what they read. What these strategies lack, though, is the means to support students in gaining critical background knowledge and vocabulary to help them more deeply understand what they read. Thus, greater emphasis must be placed on pre-reading support.

Before they begin reading a new text, several strategies can help students boost their understanding of background knowledge:

Vocabulary Selection – Identifying key vocabulary words is essential. There are multiple approaches to selecting vocabulary, and it is important to consider the purpose of each word chosen. Does it follow a decoding pattern currently being studied? Is it based on learned morphology (familiar roots or prefixes)? Is it necessary for a global understanding of the subject matter? Is it a valuable addition to a student’s personal vocabulary?

Text Knowledge – Consider the type of text the student is reading. Is it a familiar genre? Are there unfamiliar structures (such as parentheses or footnotes) that may affect comprehension?

Background Information – Teachers must determine what background knowledge is necessary for understanding. Does the historical context require explanation? Are there references to unfamiliar ideas, concepts, or other texts? Are there cultural or social norms that may be unfamiliar to the student? What should students know about the author to understand the context in which they are writing? What biases or perspectives are being presented?

Skimming and Scanning – While much of the above can be guided by the teacher, students should also take an active role in previewing the text. What unfamiliar words can they identify? What do they notice about the structure or format (e.g., chapter titles, bold section headings)?

While this list may seem extensive, it is not intended as a rigid checklist for every text. Instead, it provides a framework that allows for the integration of multimodal approaches. Teachers should explore pre-reading activities that engage multiple modalities, such as watching video clips, listening to audio recordings, or analyzing primary sources. Effective pre-reading activities not only equip students with the necessary tools to navigate unfamiliar texts but also foster enthusiasm and engagement in the reading process.

References

“Building Knowledge Can Help Build Comprehension Success.” International Dyslexia Association, 26 July

2021, dyslexiaida.org/building-knowledge-can-help-build-comprehension-success/.

“Models of Reading.” Reading Rockets,

www.readingrockets.org/reading-101/how-children-learn-read/models-reading. Accessed 27 Mar. 2025.