Spelling is Hard

For many students with language-based learning disabilities, learning to spell can be emotional. It may be hard because, too often, students have been raised on flashcard learning and rote spelling tests which have permanently established a punishing all-or-nothing dichotomy of right and wrong through visual memory. Even for the student who has successfully begun to encode by applying learned linguistic concepts, spelling can be hard because dictated words are employed out of context in a stilted routine easily upstaged by the engaging characters and experiences they encounter reading books.

Teaching spelling can also be emotional. It can be hard for the educator to prioritize this essential activity as spell check and autocorrect become smarter, more integral supports within our primary modes of modern communication (like texting and email). Even for the teacher who has successfully integrated technology, spelling is hard because the tools available for monitoring and correcting certain typos cannot support students who routinely omit syllables or use such irregular (vs. phonetic) formations; most suggestions are rendered irrelevant or nonexistent.

However, practicing spelling is crucial. A good speller possesses a solid understanding of language structure (sound-symbol correspondence, word parts and morphemes, etymology) making them an inherently more well-informed and fluent reader. Not only that, students who encode words automatically from their orthographic memory are freer to focus more cognitive energy on comprehending text, thinking critically, and generating higher-level ideas.

For teachers seeking to improve the quality of their spelling instruction, it is essential to acknowledge that English is far more predictable than most believe it to be. According to research, only about 4% of English words can be classified as truly irregular. Thus, good spelling instruction must provide students with a logical framework within which to reliably make informed choices. Equally, support identifying and memorizing irregularities (or irregularities for now) must be provided in tandem with systematic exposure to predictable linguistic concepts.

Games for Spelling Success

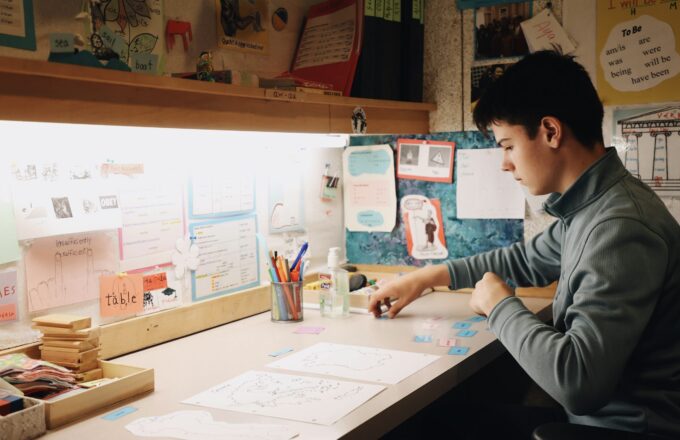

In my experience, manipulative activities that involve pictures as dictation prompts can make the process of reinforcing this framework more engaging and participatory. A colorful, fun platform can contribute to a less fraught experience, and a collaborative approach can empower the student to make connections. Still, activities must be purposefully scaffolded in order to gradually foster independence and incrementally add challenge.

Students might begin to strengthen their phonemic awareness by identifying the initial consonant found in a pictured word. To start, students draw cards featuring images of a rhino, kangaroo, and penguin. They move their token to the corresponding graphemes r, k, p as written on the game board. The student is supported by seeing the graphemes but must still match and differentiate independently. To increase the challenge, have students roll a dice, land on a pictured word, and generate the initial grapheme on an accompanying sheet by themselves. For additional challenge, try using snake, frog, flamingo. These words require the student to break apart a consonant blend in order to isolate the initial sound. If pictures are chosen carefully, the same process can be followed to help students strengthen their understanding of final consonants.

A similar approach may be used as students advance to learning such spelling expectancies as the -k/-ck rule. To start, students draw cards featuring pictures of words that end with -k or -ck and move to the correct written grapheme on the game board. Play advances to them encoding the entire word using known rules after landing on the image. Ramp up the challenge by using pictures that represent two-word phrases such as thick book, black sock, or pink drink. Encourage the students to use the rule and name the picture themselves. To reduce any possibility of memorization, try using novel prompts for the same images. For example, match the previous pictures to new phrases like black book, sleek sock, and pink milk to keep players thinking actively. Provided such opportunities for review, students may become invested in generating (and even drawing!) words that fit the game’s theme, evidencing their understanding.

Handling Common Complications

As students segue into work with multisyllabic words, scaffolding for success can look both similar to work with single syllable words and different. Like before, teachers may require students to spell targeted word parts, such as affixes or certain isolated syllables, before asking that they spell the whole word in order to ease the cognitive load. For example, students navigating a game board with pictures of consonant -le words (e.g., marble, duffle, apple) may be asked to spell just the endings -ble, -fle, and -ple, during the first round. Alternatively, teachers may provide the spelling of a word part in order to support a student whom they are asking to spell the entire word. In this case, students maneuvering a game board featuring pictures of words that end in -tion or -ture may be allowed to copy from visual aids printed with the affixes during the first round.

But let’s be honest, there’s not an easy clipart or graphic for every dictation word. More than once, I’ve had to make a key for a game board so that I don’t forget the intended words behind activities I’ve created myself! For occasions when picture prompts just don’t fit, try pairing your dictation with an activity that models and rewards students for planning ahead. A game board can emphasize the logic behind any dictated word by requiring the student to demonstrate their systematic approach prior to encoding. For example, before spelling their word on a white board or lined paper, a student moves the number of spaces that correspond to the total sounds or syllables heard. Similarly, the student could verbalize each syllable type or name affixes involved and move accordingly. Advancing two or more spaces makes it extra fun!

There are many variables that complicate the learning and teaching of spelling. Reinforcing concepts using game-format activities can reduce negative emotions as teachers and students alike become invested in the study of spelling through preparing (drawing!), playing (spelling!), and winning (growing academically!) at relevant games.

References

- Joshi, R.M., Treiman, R., Carreker, S., and Moats, L.C. (2008). “How Words Cast Their Spell”. American Educator. Volume 32, no. 4. Winter 2008-2009.

- Moats, L.C. (2005). “How Spelling Supports Reading.” American Educator. Volume 29, no. 4. Winter 2005-2006.