Defining LBLD

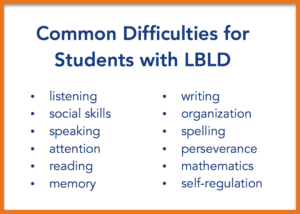

Language-based learning disability (LBLD) refers to a spectrum of difficulties related to the understanding and use of spoken and written language. LBLD is a common cause of students’ academic struggles because weak language skills impede comprehension and communication, which are the basis for most school activities.

Like all learning disabilities, LBLD results from a combination of neurobiological differences (variations in the way an individual’s brain functions) and environmental factors (e.g., the learning setting, the type of instruction). The key to supporting students with LBLD is knowing how to adjust curriculum and instruction to ensure they develop proficient language and literacy skills. Most individuals with LBLD need instruction that is specialized, explicit, structured, and multisensory, as well as ongoing, guided practice aimed at remediating their specific areas of weakness.

LBLD can manifest as a wide variety of language difficulties with different levels of severity. One student may have difficulty sounding out words for reading or spelling, but no difficulty with oral expression or listening comprehension. Another may struggle with all three. The spectrum of LBLD ranges from students who experience minor interferences that may be addressed in class to students who need specialized, individualized attention throughout the school day in order to develop fluent language skills.

Emergence and Signs of Language-Based Difficulties

Children naturally develop skills at their own pace, and most students have difficulty learning from time to time. To assess whether a student’s performance in a skill area warrants concern, we must take into account typical development patterns. We expect preschool children to have difficulty tying their shoes, cutting out pictures from magazines, adding numbers, and writing neatly. Middle school students should be able to do these things quite easily. It is persistent difficulty in one or more skill areas that requires investigation. Even so, the level of struggle that calls for investigation does not emerge at a predictable time in child development; rather, difficulties may appear at any time from preschool through adulthood.

While some students with language-based learning disabilities are diagnosed very young, many other students progress through early elementary school with few issues. As they transition into middle school, high school, or even college, the demands for language rise, as do expectations for independent learning. Students who perform competently in structured, skills-based, supportive classrooms may find themselves floundering as they try to manage their school and homework with less individual guidance from teachers. They may suddenly seem anxious, frustrated, angry, or defeated about school. This level of change warrants investigation, and should not automatically be attributed to typical adolescent behavior.

Sometimes difficulties emerge because the compensatory strategies students used in the past stop working. Many bright students with learning disabilities go to great lengths to mask their struggles. Their intelligence enables them to compensate for lack of skill in one area with talents in other areas. A student might be a terrific talker and demonstrate solid knowledge in class discussions. Why would the teacher guess this student cannot read fluently? While students’ capacity to adapt is admirable, the cost is high. Too often, they enter middle and high school with elementary-level reading and writing skills.

Many screening assessments are commercially available, and easy to administer and score. Curriculum-based measurement (CBM) can also be used to screen students. Excellent free resources for CBM are available online at www.interventioncentral.org. In addition to screenings, students offer a rich source of information about their learning strengths and struggles – if we take the time to ask. The attached learning questionnaires show one example of how to ask students to self-report.